In the annals of architectural grandeur, few edifices can rival the Palace of Versailles, that shimmering monument to French regal ambition. From its genesis as a humble hunting lodge, it ascended to become the nec plus ultra of monarchical majesty, a lodestar for every king, duke, earl, and baron who ever dared to etch their name in marble across Europe’s courts. Yet, as the guillotine’s merciless blade severed the aspirations of France’s nobility, Versailles endured—not merely as a relic, but as a towering testament to human artistry, aspiration, and that most intoxicating of vices, hubris.

Louis XIII’s rustic retreat

Imagine a time when Versailles was not the gilded colossus we know today but a mere speck in the landscape. In the early 17th century, Henri IV, that most jovial of monarchs, hunted in its wooded environs, entertained in a feudal dwelling by the Maréchal de Retz. Yet it was his son, Louis XIII, who planted the seed of Versailles’ destiny. In 1624, he acquired a modest plot and erected a hunting lodge—a structure so unassuming that the waspish Duke of Saint-Simon dismissed it as “a very miserable cabaret, a windmill, and this little house of cards.” The Marquis de Sourches, with equal disdain, called it “a small gentleman’s castle.”

This primordial château was a utilitarian affair: a main building flanked by two wings, encircling a square courtyard, with a portico of seven arches and a moat that seemed to apologise for its lack of water. Attributed to Salomon de Brosse, it was less palace than pastoral idyll, complete with dovecote, sheepfold, and stables—a farmstead for a king who sought solace from the intrigues of court. Its gardens, designed by Claude Mollet and Jacques Boyceau, were adorned with “broderies” of trimmed boxwood and coloured lawns, but the park remained a hunter’s domain. Here, in 1630, the infamous “Journée des Dupes” unfolded, cementing Cardinal Richelieu’s ascendancy and proving that even a humble lodge could stage the dramas of power.

Here comes the Sun King

With the death of Louis XIII in 1643, Versailles fell into a brief slumber, a forgotten relic. But then the new king Louis XIV, cast his glorious gaze upon it. The year 1661 was a fulcrum in its history, sparked by the young king’s visit to the château Vaux-le-Vicomte, the creation of the ill-fated Nicolas Fouquet, till that moment one of his confidences. Enraptured – and offended- by its splendour – a Gesammtkunstwerk avant la lettre by architect Louis Le Vau, gardener André Le Nôtre, water-wizard François Francine, and decorator Charles Le Brun – the Sun King resolved to outshine it. He summoned the same virtuosos to Versailles, and thus began its metamorphosis into a monument of divine kingship.

The transformation was swift and audacious. The modest forecourt of Louis XIII was razed, replaced by a sprawling esplanade framed by kitchens and stables. Le Vau conjured the first Orangery, a verdant cathedral to house 1,250 orange trees pilfered from Vaux. Le Nôtre sketched the embryonic lines of the gardens, with their parterres and the Grand Rondeau, later to become the Bassin d’Apollon. Louis XIV, ever the micromanaging monarch, was a constant presence, issuing directives with the zeal of a man possessed. By September 1663, Versailles hosted its first grand courtly spectacle—balls, ballets, Molière’s comedies, and hunts—where the king played host with unprecedented largesse, furnishing apartments and provisions for all.

As the decades unfurled, Versailles burgeoned into a mirror of Louis’ reign. Le Vau swathed the original château in new façades, birthing the Grand Apartments and the Escalier des Ambassadeurs, each surface ablaze with symbols of the Sun King’s glory. From 1678, Jules Hardouin-Mansart took the reins, erecting the Hall of Mirrors and vast wings to house the swelling court. In 1682, Versailles became the seat of government, its grandeur a testament to French artistic supremacy, eclipsing even Italy’s influence. Palaces across Europe, from Vienna to St. Petersburg, aped its style, even as their masters cursed Louis’ name.

The refinements and ravages of the 18th century

The death of the Sun King in 1715 left Versailles a finished canvas, its exterior lines largely fixed. Yet under Louis XV and Louis XVI, its interiors were reshaped to suit the shifting mores of royalty. Louis XV, with his penchant for privacy, commissioned Robert de Cotte’s Salon d’Hercule and Gabriel’s Opera House, but also desecrated sacred spaces like the Escalier des Ambassadeurs for his own comfort. He dreamed of remaking the château’s core in a Greco-Roman idiom, but penury curtailed his ambitions, leaving only the “fâcheuse aile Gabriel” as a half-realised testament. Louis XVI, constrained by looming revolution, could do little but replant the park, his grander visions thwarted by an empty treasury.

Stage for historical drama’s

Not only was Versailles the stage where the Sun King reveled in Molière’s plays and Lully’s ballets, but it has also served as a dramatic arena in subsequent centuries. The 18th century saw Versailles entangled in the tides of revolution. In 1789, the Women’s March on Versailles—a furious procession of Parisian market women and revolutionaries—compelled Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette to abandon the palace for Paris, heralding the monarchy’s collapse. The palace, stripped of its royal pulse, fell silent, its opulence a hollow echo of lost glory.

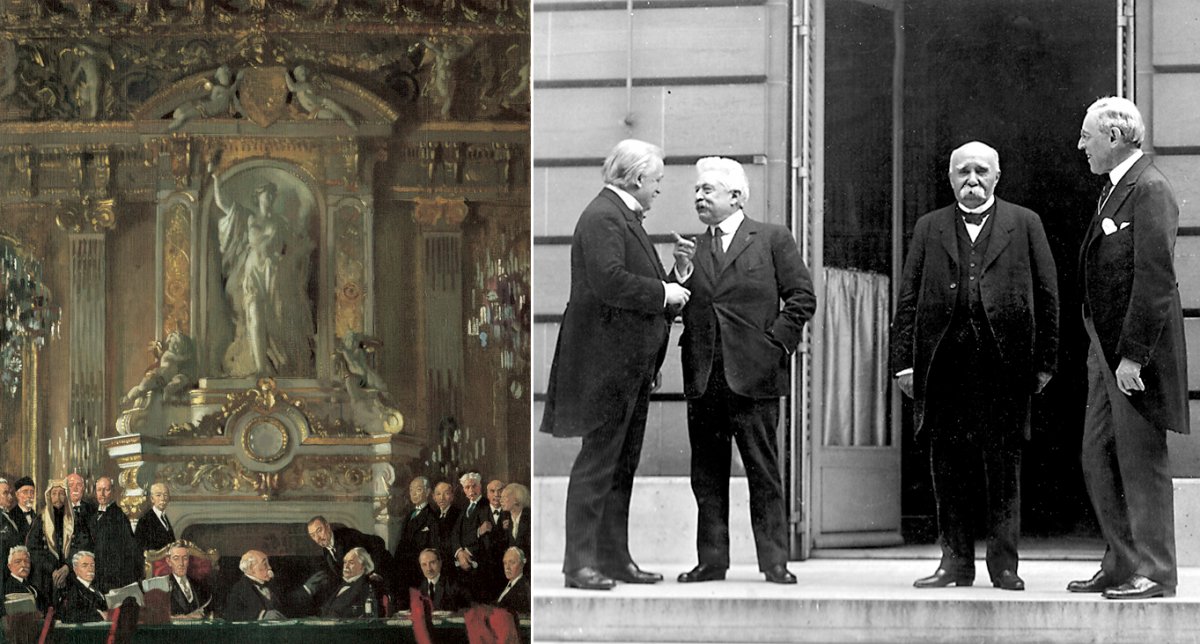

In 1871, following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the proclamation of the German Empire was audaciously staged in the Hall of Mirrors, a deliberate affront to French pride. Half a century later, in 1919, the same hall hosted the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I but sowed seeds of future conflict with its punitive terms. These twin events, one of hubris and the other of retribution, underscore Versailles’ role as a mirror to history’s caprices.

From royal seat to national shrine

The French Revolution of 1789 extinguished Versailles’ role as a living palace. Napoléon toyed with residing at Trianon, and Louis XVIII dabbled in restorations, but it was Louis-Philippe who, in 1837, redefined its purpose. Declaring it a museum “to all the glories of France,” he preserved Versailles from ruin, yet his zeal led to regrettable demolitions and the dispersal of priceless artworks. Today, it serves as a ceremonial seat for the French Parliament and a repository of decorative art—a “great ruin and a great tomb,” as one observer once poignantly remarked.